The frontier of science is a wild and lawless place. Like all badlands, it attracts visionaries, charlatans and the dispossessed. Far from the jurisdiction of law enforcers, isolated communities cluster together and thrive in quiet obscurity. No group however, is quite so strange as the bio-hackers. So, pack your wagon and keep you revolver close as we venture into transhumanist territory and meet a few of the locals.

Superhuman, an exhibition currently at the Wellcome Collection, seems like a good place to start. The show, themed around human enhancement, features dozens of examples of humanity attempting to repair or replace function lost through illness or injury. This approach has traditionally been the focus of medicine and the biological sciences.

However, there have always been small groups of people who sought to go beyond this paradigm. The instinct to add and augment can be seen throughout history, particularly when it comes to aesthetics. Jewelry, makeup and clothing are very familiar examples of this instinct to artificially change ones image.

Less common, are procedures that integrate an enhancement more directly with the body. We recognise tattoos and piercings as fairly normal and many believe bionic devices to be a natural extension of these ancient practices. Now, with technology offering real potential to move beyond aesthetic enhancements towards ones that give us new or improved abilities, there are some that believe a tranche new of functional implants and modifications are on the way. Does it, however, follow that merely because we have the technology, we should use it?

Largely, dreams of a new bionic dawn remain in the realm of science fiction, due to cost, legality, ethical concerns or the harsh reality of what is possible. Occasionally however, these realms do drift closer to realty. Out there on the fringes is where things get a little weird. Black-and-white morality starts to give way to some rather uncomfortable shades of grey.

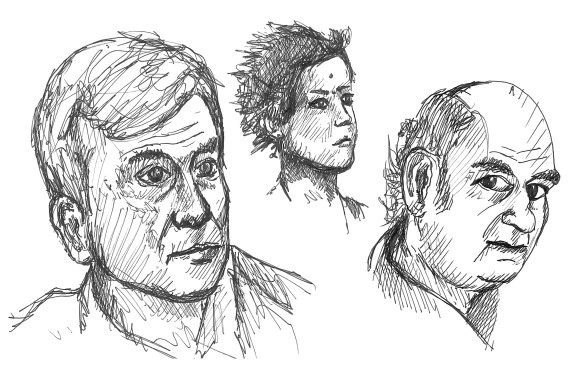

Inspired by the exhibition, I set out to find individuals who have voluntarily elected to have surgery to implant electronic or electrical devices into their body. I found three: one academic, one artist and one amateur. Two of them are well known, while the other is not. Their methods and backgrounds are all different, so what lies behind their seemingly bizarre actions? Is it conviction, curiosity or a disturbing 21st century manifestation of self-harm?

Kevin Warwick – The scholar

Kevin Warwick – The scholar

Professor Kevin Warwick is currently a researcher in cybernetics at the University of Reading. His work in cybernetics and direct communication between man and machine has often been sensationalist and attention grabbing. Warwick’s seemingly outlandish predictions have included warnings of robot take-overs and cyberdrugs, downloadable from the Internet.

Despite accusations of being a “media junkie” Warwick has undoubtedly produced some good research in robotics, control systems and bioengineering. It is probably this dichotomy that has lead to his anointment, by Wired’s Leander Kahney, as one of the most famous living scientists. At some point he decided to stop talking about the future and try to drag it into the present.

Much of his work relevant to this article has involved serious attempts to implant devices with the help of surgeons. Some of his initial work, performed in the late 1990s involved the implantation of radio frequency identification (RFID) devices. These allowed him to interact with items in his environment. Doors would open as he approached and his computer was engineered to function only in his presence. The successful completion of this experiment led Warwick to memorably declare himself “the first cyborg”.

In later experiments Warwick was implanted with an array of tiny electrodes. These were placed in such a way that they directly monitored impulses traveling along the median nerve in his arm. The device transmitted a signal to an external receiver, which was used to control a robotic hand. The robotic hand was able to directly mimic the movement of his own.

Finally his wife was roped in. Both with matching implants, they were able to sense the movement in each other’s arms, through their own corresponding limb. The setup was clumsy, and certainly not the telepathic communication Warwick claimed, more the sensation of a jolt corresponding to movement in the other person. It is often easy to question Warwick’s claims, but very difficult to doubt his enthusiasm.

“I feel that we are all philosophers, and that those who describe themselves as a ‘philosopher’ simply do not have a day job to go to” – Kevin Warwick (Times 2000)

Stelarc – The artist

Stelarc – The artist

Stelarc, now in his mid-60s has been undisputed king of transhumanist themes in art for decades. His career as a performance artist stretches back to the early 70s when he first began experiments to extend capabilities of the human body.

Early work saw the artist suspend himself above a live audience. He tethered himself using flesh hooks that penetrated the skin, causing considerable pain. Often these performance incorporated robotic devices designed by the artist to move and rotate his body in the air.

Stelarc’s ear on arm project, now ongoing for a decade, has represented some of his most extreme work. He persuaded surgeons to implant a polymer scaffold replica of his left ear under the skin on his arm. Placed inside the arm with it was a microphone, capable of recording and transmitting sound from within the “new ear”. After several major surgeries and a serious bout of infection the project is still not complete.

“The ear also might be a kind of distributed Bluetooth system, where if you telephone me on your cellphone, I’ll be able to speak to you through my ear. But because the small speaker and the small receiver would be implanted in a gap between my teeth, I would hear your voice in my head. If I keep my mouth closed, only I hear your voice. If I open my mouth and someone else is close by, they might hear your voice seemingly coming from my mouth. And if I lip-sync, I’d look like some bad foreign movie.” – Stellarc (Wired 2012)

Lepht Anonym – The zealot

Lepht Anonym – The zealot

Lepht is the odd one out. She is young, female and relatively obscure. She is not a professional and she is most certainly not an establishment figure. Most people would think her actions were dangerous, self-destructive and symptomatic of an underlying mental health condition. On her personal blog she does indeed document an opiate addiction and occasional depressions.

However, in 2010 this mysterious online entity manifested herself at hacker conference in Berlin, after which she received some press attention. She discussed experiments she had performed on herself to implant object bellow her skin. After the refusal of doctors to assist her, she began to operate on herself.

She operated in her kitchen with whatever came to hand and without anesthetic. Using kitchen knives and later scalpels she first experimented with RFID tags, sterilising instruments with vodka. The pain was excruciating and the mistakes were plenty. Yet for Lehpt it was not enough. “RFID is crap as a personal security system,” She said in Berlin “It’s really only a way to experiment with the implant techniques.” (27C3 2012)

Later she began to place neodymium magnets into her fingertips. Currents induced in the magnets innervated the nerves, giving her the ability to sense electrical fields. Further down the line she plans to introduce and innate sense of direction by implanting an electronic compass.

As a bioengineer, with some knowledge of electronics, biocompatibility and physiology these experiments fascinate and horrify me in equal measure. Things do not look good for Lepht. If her recent, increasingly sporadic blog entries are to be believed her mental and physical health are deteriorating.

It would be all too easy to dismiss Lepht in particular as delusional. What she is doing is unquestionably harmful and cannot and should not be encouraged in any way. However, her writing seems too lucid and consistent to simply represent a psychotic delusion. Something else must be going on.

Brave new world or dead end?

The first obvious question is over the significance of these people’s actions. Given that we have been microchipping our cats and dog for years, what is the actual significance of the experiments described above? The difference as I see it is that the implants discussed are active. In each case the sensory or manipulative capabilities of the individual are extended or modified and have implications for the mental and physical environment that they inhabit.

If they truly are extending the biology they inherited from their ancestors in a way they will be directly conscious of, it is possible to imagine massive implications. If bio-hacking becomes more popular or acceptable, it is all the more worrying that there is no consensus on the outcomes or societies response to these reckless pioneers.

To begin forming these our own opinions one approach is simply to study the cases of Warrick, Stellarc and Anonym. What is it that separates the actions of these three people? How can we determine where to draw the lines and make the moral judgments? These are not questions I necessarily feel I can answer. I simply have not made up my own mind although, it is difficult not to admire the bravery and vision of people who go to such great lengths to test an idea or realise a dream.

I will say that you might consider drawing parallels with drug experimentation in the sixties. People were using newly available substances like LSD to seek “higher levels of consciousness”. Experimentation stemmed from a naïve curiosity and occasionally a rational inquisitiveness.

However failure of parts of society to engage meaningfully with new substances and those who imbibed them lead to major pitfalls. Policy makers made reactionary regulatory decisions too late. Drug users were equally culpable in terms of recalcitrant actions and unsupported rhetoric. The result was a complicated mess, a generation casualties and endemic illegal drug use.

If we are to avoid the same mistakes we need to agree collectively on an attitude to transhumanist ideals. Policy must not marginalise those who choose to express their rights over the treatment of their own bodies. Ignoring or dismissing the users of new technology has seldom proved a sustainable in the past.

This text was originally written for the Wellcome Trust Blog (22/08/12)